Dream and Story Hunters

09/06/15 10:31 Filed in: Logbook

Johann's real name is actually Hans. He isn't a Catholic priest or a Buddhist monk; he's a Methodist pastor. I meet him in Chiang Mai, Thailand's second largest city, rather than the isolated village where I had been expecting to find him.

Which shows that causality and chance can coexist. It's an effect of the uncertainty principle coined by Heisenberg, one of the legends of my personal cosmology, of those mysteries that I don't understand but which lend themselves to many interpretations. Not to mention that the very name is extraordinarily fascinating and evocative.

Heisenberg's Uncertainty Principle. Photograph: Alamy

But let's start at the end (which isn't actually the end). So, I meet Hans or Johann, who turns out to be neither whom nor where I expected him to be. How it happens and why is the plot for a story that is waiting to be told. A story that begins in an Italian restaurant in Bangkok, where I hear a priest or a monk, who for almost thirty years has lived "somewhere near the Burmese border", moving between the Karen villages dotted around the mountains in the area.

This is just the start of a series of events that kicked off then and continued in an apparent cause and effect link. But they were also entirely random, determined by my freely made personal choices, and often pure impulses. The uncertainty principle magically brings with it a concept of self-determination.

That's how it happened for Hans: many years ago he chose to be a missionary in Thailand because he was interested in Buddhism and had read Siddhartha. He came to the isolated Karen village, even more isolated than where I looked for him, by pure chance. "There were so many open doors," he says. Once through the door to the village, still protected by the Spirits, he had to find a point of contact with the Karen people, a way of communicating the Word. He found it by studying their legends and their dreams, which he compares to those in the Bible (there are actually many similarities, beginning with the name of God: Y'wa, for the Karen).

So, at the Thai-Vietnamese restaurant where we spend the early afternoon, I am reminded of Jung's archetypes and Freud's dreams, Jeremiah's lamentations, the wi and the k’thi thra, the Karen prophets and shamans with their Spirits. Interesting and engaging company.

I mull over and slightly regret the meetings and characters that preceded them and that led me here. The Italian calling himself an adventurer with many stories to tell, the young Karen priest who doesn't understand what I'm looking for, the apparition of a charming Bernadette.

"The funny thing is I don't know who I'm looking for, but it's good to set off at dawn to do it," I noted down on the morning I began following this story. It was as though, for the umpteenth time, I were trying to trigger my own personal butterfly effect. By getting on an old bus rather than with a flutter of wings.

"In the end, it's about believing in God," says Hans.

I believe. And I thank him for this story.

Les Philosophes, by Joan Mirò

Which shows that causality and chance can coexist. It's an effect of the uncertainty principle coined by Heisenberg, one of the legends of my personal cosmology, of those mysteries that I don't understand but which lend themselves to many interpretations. Not to mention that the very name is extraordinarily fascinating and evocative.

Heisenberg's Uncertainty Principle. Photograph: Alamy

But let's start at the end (which isn't actually the end). So, I meet Hans or Johann, who turns out to be neither whom nor where I expected him to be. How it happens and why is the plot for a story that is waiting to be told. A story that begins in an Italian restaurant in Bangkok, where I hear a priest or a monk, who for almost thirty years has lived "somewhere near the Burmese border", moving between the Karen villages dotted around the mountains in the area.

This is just the start of a series of events that kicked off then and continued in an apparent cause and effect link. But they were also entirely random, determined by my freely made personal choices, and often pure impulses. The uncertainty principle magically brings with it a concept of self-determination.

That's how it happened for Hans: many years ago he chose to be a missionary in Thailand because he was interested in Buddhism and had read Siddhartha. He came to the isolated Karen village, even more isolated than where I looked for him, by pure chance. "There were so many open doors," he says. Once through the door to the village, still protected by the Spirits, he had to find a point of contact with the Karen people, a way of communicating the Word. He found it by studying their legends and their dreams, which he compares to those in the Bible (there are actually many similarities, beginning with the name of God: Y'wa, for the Karen).

So, at the Thai-Vietnamese restaurant where we spend the early afternoon, I am reminded of Jung's archetypes and Freud's dreams, Jeremiah's lamentations, the wi and the k’thi thra, the Karen prophets and shamans with their Spirits. Interesting and engaging company.

I mull over and slightly regret the meetings and characters that preceded them and that led me here. The Italian calling himself an adventurer with many stories to tell, the young Karen priest who doesn't understand what I'm looking for, the apparition of a charming Bernadette.

"The funny thing is I don't know who I'm looking for, but it's good to set off at dawn to do it," I noted down on the morning I began following this story. It was as though, for the umpteenth time, I were trying to trigger my own personal butterfly effect. By getting on an old bus rather than with a flutter of wings.

"In the end, it's about believing in God," says Hans.

I believe. And I thank him for this story.

Les Philosophes, by Joan Mirò

0 Comments

Monsoons, migrations, horrors and values

28/05/15 13:26 Filed in: South-East Asia

It is monsoon season in Southeast Asia, but the flow of migrants continues across the Bay of Bengal from the coast of Bangladesh towards Malaysia and Indonesia.

Monsoons and migrations happen on a repeated cycle, like natural phenomena. And as such they are interconnected and variable. This year, the monsoon in the south east seems milder than normal. So the number of boats packed with migrants is on the up: these are the last few days before conditions worsen. Then it won't be possible to set sail and the sea and the rains will flood the “land of tides”, creating yet another environmental disaster that will further add to the numbers seeking to escape.

The majority are Rohingya. There are about one million of them, all Muslims, settled in northern Rakhine, a Burmese state on the Bay of Bengal. They are the unwanted of Southeast Asia. They are also part of this natural cycle, in an inescapable fate of poverty, slavery, escape, capture, escape.

When this monsoon season ends, the dead will once again be counted and the horrors related. But, in the end, the story is always the same. I read today's reports (such as these two articles by Il Foglio and Wall Street Journal, which feature singular coincidences). I reread old articles, including my 2009 report on the Rohingya refugee camps in Bangladesh (here, in Italian). Not much has changed. Some things have got worse: from news of mass graves discovered in the forest between Thailand and Burma, to the new persecutions in Burma.

Many have compared this to the tragic situation of migrants in the Mediterranean. Some say it is just another form of globalisation. In fact, it is a sign of how divided the world is. Aside from all cultural conformism and despite many ambiguities, the West is demonstrating that its “universal values” are still the strongest.

Photo by Andrea Pistolesi, from: Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh

Monsoons and migrations happen on a repeated cycle, like natural phenomena. And as such they are interconnected and variable. This year, the monsoon in the south east seems milder than normal. So the number of boats packed with migrants is on the up: these are the last few days before conditions worsen. Then it won't be possible to set sail and the sea and the rains will flood the “land of tides”, creating yet another environmental disaster that will further add to the numbers seeking to escape.

The majority are Rohingya. There are about one million of them, all Muslims, settled in northern Rakhine, a Burmese state on the Bay of Bengal. They are the unwanted of Southeast Asia. They are also part of this natural cycle, in an inescapable fate of poverty, slavery, escape, capture, escape.

When this monsoon season ends, the dead will once again be counted and the horrors related. But, in the end, the story is always the same. I read today's reports (such as these two articles by Il Foglio and Wall Street Journal, which feature singular coincidences). I reread old articles, including my 2009 report on the Rohingya refugee camps in Bangladesh (here, in Italian). Not much has changed. Some things have got worse: from news of mass graves discovered in the forest between Thailand and Burma, to the new persecutions in Burma.

Many have compared this to the tragic situation of migrants in the Mediterranean. Some say it is just another form of globalisation. In fact, it is a sign of how divided the world is. Aside from all cultural conformism and despite many ambiguities, the West is demonstrating that its “universal values” are still the strongest.

Photo by Andrea Pistolesi, from: Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh

The Theatre of Stories

26/03/15 12:07 Filed in: South-East Asia

"Is it true Thomas Merton was staying at the Oriental a few days before his death?"

"If he had been staying here, he wouldn't have died. No one dies at the Oriental."

It's a brief conversation but it has many meanings, at least for me. It reminds me of people such as that Trappist monk who studied oriental religions or the elderly lady who spent her whole life at the legendary Bangkok hotel reminiscing of meetings with writers and secret agents. It triggers a sequence of lost stories rediscovered in travel journals, published and unpublished articles, and little notes.

All of this just to talk about a book: "Sophisticated stays in Southeast Asia".

Initially, I'll admit, it seemed excessive to me. In the end it's just a book about hotels, no matter how fascinating and “smart” they may appear. However, the book did involve a great deal of work and lots of travelling. The photographer Andrea Pistolesi and I thought it was worth presenting to the best of our ability. So, little by little, while looking for ideas, I realised the book is not merely a collection of hotels; it's a concentration of stories that happened at those places and that continue to replicate with different characters.

I remember something Matsuo Basho wrote: “I decided to note down my impressions in no particular order, just like the ramblings of a drunkard or a person talking in their sleep, about the unforgettable places I visited: do not give me all that much attention…”.

At this point I'd better reproduce the introduction to the book.

"There is the culture of luxury and the luxury of culture," a wise man once said. He was no hermit or philosopher, but the director (and a bit of a hermit and philosopher) of a hotel at the foot of the Himalayas (so not featured here). His aphorism is useful for understanding the spirit of this book: “the luxury of culture”. The hotels featured here are luxurious, at times extremely so. But luxury does not just mean excellence or exclusivity; it can also describe a place that enables us to live in the moment, to appreciate the natural and cultural space in which we find ourselves. They are places of eminent history, art or design because they are indicative of a trend. Unlike “non-places”, spaces devoid of identity, these are charged with meaning; they are remarkable spots on the Asian landscape, models of that architecture and life style that is redefining the Orient and spreading from there to the West. Intelligent places.

That being said, this book is not aiming to be any kind of guide. Nor does it claim to be comprehensive (over time, who knows, given it is a work in progress). In order to be featured here, the hotels must have been actually visited and experienced by us. The idea is luxurious in its very simplicity: to offer a useful tool for sophisticated travellers. For those discerning travellers for whom a hotel is not just a place to go to (or to get bragging rights from), but a part of the journey. Intelligent travellers.

“Sophisticated stays in Southeast Asia” can be downloaded as an e-book from various platforms (at a cost of approximately 4 euro) or ordered in print (32 euro). Also available in English. All references here

"If he had been staying here, he wouldn't have died. No one dies at the Oriental."

It's a brief conversation but it has many meanings, at least for me. It reminds me of people such as that Trappist monk who studied oriental religions or the elderly lady who spent her whole life at the legendary Bangkok hotel reminiscing of meetings with writers and secret agents. It triggers a sequence of lost stories rediscovered in travel journals, published and unpublished articles, and little notes.

All of this just to talk about a book: "Sophisticated stays in Southeast Asia".

Initially, I'll admit, it seemed excessive to me. In the end it's just a book about hotels, no matter how fascinating and “smart” they may appear. However, the book did involve a great deal of work and lots of travelling. The photographer Andrea Pistolesi and I thought it was worth presenting to the best of our ability. So, little by little, while looking for ideas, I realised the book is not merely a collection of hotels; it's a concentration of stories that happened at those places and that continue to replicate with different characters.

I remember something Matsuo Basho wrote: “I decided to note down my impressions in no particular order, just like the ramblings of a drunkard or a person talking in their sleep, about the unforgettable places I visited: do not give me all that much attention…”.

At this point I'd better reproduce the introduction to the book.

"There is the culture of luxury and the luxury of culture," a wise man once said. He was no hermit or philosopher, but the director (and a bit of a hermit and philosopher) of a hotel at the foot of the Himalayas (so not featured here). His aphorism is useful for understanding the spirit of this book: “the luxury of culture”. The hotels featured here are luxurious, at times extremely so. But luxury does not just mean excellence or exclusivity; it can also describe a place that enables us to live in the moment, to appreciate the natural and cultural space in which we find ourselves. They are places of eminent history, art or design because they are indicative of a trend. Unlike “non-places”, spaces devoid of identity, these are charged with meaning; they are remarkable spots on the Asian landscape, models of that architecture and life style that is redefining the Orient and spreading from there to the West. Intelligent places.

That being said, this book is not aiming to be any kind of guide. Nor does it claim to be comprehensive (over time, who knows, given it is a work in progress). In order to be featured here, the hotels must have been actually visited and experienced by us. The idea is luxurious in its very simplicity: to offer a useful tool for sophisticated travellers. For those discerning travellers for whom a hotel is not just a place to go to (or to get bragging rights from), but a part of the journey. Intelligent travellers.

“Sophisticated stays in Southeast Asia” can be downloaded as an e-book from various platforms (at a cost of approximately 4 euro) or ordered in print (32 euro). Also available in English. All references here

Between Europe and Asia

10/03/15 15:07 Filed in: South-East Asia

Day after day, divided between Asia and Europe for reasons beyond my will but not my choice, I take notes, write, make plans. I try to grasp signs of connection between the two worlds, if only to give some meaning to this state of limbo.

Sometimes stories find their own way, sometimes they don't. I often forget them anyway. But they keep on living, more or less latent in my archive. Sometimes they pop up serendipitously while I'm looking for something else.

That's what happened with an article about the Asia-Europe Meeting, held last October in Milan. I attended the meeting and wrote the article to try to give a professional meaning to my stay in Italy and because I thought it would be interesting to observe a spectacle I normally follow in Asia from another perspective. But the article turned out to be too abstract, too obscure, perhaps precisely because I was outside my comfort zone.

Reading it again in Bangkok, though, I found its shadows came into sharper focus. So much clearer than what is actually happening on a global scale. It's a spectacle of lights and shadows that I want to expose here on Bassifondi.

“Overshadow”. This is the oft-repeated mantra and the formula for understanding the Asia-Europe Meeting (ASEM). In a certain sense, it was like attending a production of what in Southeast Asia is known as the “theatre of shadows”, the Cambodian “Sbaek Thom”: every shadow can tell a story and the puppeteers themselves question the meaning of the shadows they create.

The tenth edition of ASEM, the two-yearly forum launched in 1996 to reinforce cooperation and dialogue between Europe and Asia, was held in Milan, Italy, in October. It was attended by Heads of State, ministers and civil servants from 53 countries: 29 from the European Union plus Norway and Switzerland, and 22 Asian countries. Together, ASEM members account for 62.5 percent of the world’s population, 57 percent of global GDP and 60 percent of global trade. “Responsible partnership for sustainable growth and security” was the theme of this “informal platform for dialogue”: such a vast topic can lend itself to all manner of discussions on economic, political, cultural, climate and energy issues.

There were so many people and so many discussions, of which only fleeting visions and vague information were glimpsed, created a shadowy effect. In Cambodia, at the 2012 ASEAN Summit, in Bangkok where I live, at other international meetings, I saw how hard it is to decode the webs of power. But in Milan, in my home country, it was even harder. Probably because here it was more complex to establish a boundary between East and West: “What is Asia? Where does Europe end? Where do they meet or collide?”, were not rhetorical questions: at ASEM Russia came under the Asian countries while the president of Mongolia called his remote country – which will host ASEM in 2016 - a “bridge between Europe and Asia”.

In a certain sense, Russian President Vladimir Putin's geopolitical strategy, Eurasia, seemed to hold sway. Located between Western and Eastern Europe (i.e. Central Asia) and bordered to the east by Mongolia, this is the theatre in which Russia can play a proactive role in the new round of “The Great Game” (as defined in 1898 by Lord Curzon, Viceroy of India, in reference to the murky conflict between Great Britain and Russia for control of Asia). China reacts to Russia's moves with plans for a “New Silk Road”, which connects the Middle Kingdom to Germany over land via Kazakhstan, Belarus, Poland and connects with the Maritime Silk Road via Italy or Spain.

As was revealed at ASEM, all this does not help bring Europe and Asia closer together. “We talk about global interdependence, and it is real. But while, whatever the economic dynamics, each region is intellectually aware of what is going on at the other end of Eurasia, each sees the other as distant and ultimately unconnected from its concerns,” wrote George Friedman, CEO of the private intelligence corporation Stratfor.

The contemporary Great Game, then, would be more appropriately named “Tournament of Shadows”. At ASEM, the biggest shadow was cast by the crisis in Ukraine, which overshadowed any other issues. Vladimir Putin and Ukraine President Petro Poroshenko met to discuss a possible solution. To no avail. To justify “Much Ado About Nothing”, José Manuel Barroso, current President of the European Commission (until November 2014), pointed out that "it was right to discuss Ukraine here", as though the discussion could raise the meeting's profile. The real justification is that the crisis in Ukraine may increase the risk of volatility of financial markets that could impact Asia and Europe. "Stability and peace are fundamental for the economy," declared Herman Van Rompuy, President of the European Council (until December 2014).

In the Theatre of Shadows the most brightly lit scene was the economy. Despite the followers of conspiracy theory, the hundreds of Asian and European entrepreneurs attending the Asia-Europe Business Forum (AEBF), which coincided with ASEM, all agreed on the liberalisation of economies. "Europe needs Asia. A strong Asian economy is a driver for global growth. At the same time, Asia needs Europe, its technologies and its markets," declared Van Rompuy. "From an economic point of view, Asia has become the largest trading partner of the European Union, which remains the world's largest single economy. Future growth in Asia, therefore, depends on access to European markets." For Asia's part, Benjamin Philip Romualdez, President of Chamber of Mines of the Philippines, pointed out "Our growth is your opportunity". Indeed, in this second phase of globalisation (in which consumption, more than output, is shifting Eastwards), managing to compete successfully will be decisive for Europe.

In fact, Europe must attract China’s Super-consumers more than Asia in general. Due to its enormous economic surplus, China's strategies are changing: it is giving up on short-term profit and investing huge amounts of capital. The activism of premier Li Keqiang at ASEM and on the other stops on his European tour demonstrated this. China is making the most of what Li calls a “global economic recession” to acquire business bases in the Old Continent, where the price of companies has dropped and more than one government has requested help from Beijing. The Chinese premier demonstrated yet more Soft Power in his meetings with Vietnamese premier Nguyen Tan Dung, shoring up bilateral relations and strengthening trade links. Thailand has also been offered collaboration: taking advantage of the European halt on commercial negotiations following last May's coup d'état, Li pledged to cooperate with Thailand in developing roads and basic infrastructure.

In short, bilateral agreements were one of the most evident features of ASEM. Which also represents its dark side. Not so much because of the secrecy involved, but mainly because they overshadow ASEAN. The Association cannot propose itself as a sole interlocutor. In 2009 the European Commission decided to redirect its goal, placing greater emphasis on bilateral agreements with individual members of the Association, and at ASEM the European Union remained sceptical. The 2015 ASEAN Business Outlook Survey highlighted the widespread concern that the much-anticipated ASEAN Economic Community (AEC) would not be launched by the end-2015 deadline. Too many of the specified deadlines of AEC implementation have been missed and some major initiatives have not taken off. According to some observers, this is partly down to ASEAN's inability to act as a supranational organisation. For others, especially the Germans (who perhaps fear an Asian repeat of European discord), one of the biggest obstacles to the ASEAN economic community is the presence of CLMV, i.e. Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar and Vietnam - countries that will need more time to adapt to this new economic space.

Offsetting this, the European Union has pressed the accelerator on the Free Trade Agreement (FTA) between ASEAN and EU - a move aimed at countering two other hyper-agreements: the American Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) and the Chinese Comprehensive Economic Cooperation in East Asia. In ASEAN the biggest supporter of the FTA with Europe is Malaysia, which will have the presidency of ASEAN in 2015. "Malaysia will take the lead to encourage the FTA process, which was discontinued a few years ago. We hope there will be an ASEAN-EU FTA that will complete the regional integration," declared Prime Minister Datuk Seri Najib Razak.

Ahead of these macro-agreements, ASEM has forged relations that may appear marginal in the global scenario, but are fundamental for regional integration. For example, between Cambodia and Thailand. The two premiers, Hun Sen and Prayut Chan-o-cha, held their first bilateral talks, demonstrating “the right chemistry” in pushing their cooperative friendship to a new level. According to well-informed sources, the two premiers discussed the development of special economic zones (SEZ), roads, customs facilities and crossings along the border. General Prayut proposed the setting up of an initial SEZ near Cambodia’s Poipet, while Cambodian authorities will consider setting up a similar estate in their territory to boost trade. And the shared desire to set up a joint development area (JDA) in the Gulf of Thailand was an open secret.

Shadows are often misleading. What might seem overshadowed may eclipse the global threat of “Super Chaos”.

Sometimes stories find their own way, sometimes they don't. I often forget them anyway. But they keep on living, more or less latent in my archive. Sometimes they pop up serendipitously while I'm looking for something else.

That's what happened with an article about the Asia-Europe Meeting, held last October in Milan. I attended the meeting and wrote the article to try to give a professional meaning to my stay in Italy and because I thought it would be interesting to observe a spectacle I normally follow in Asia from another perspective. But the article turned out to be too abstract, too obscure, perhaps precisely because I was outside my comfort zone.

Reading it again in Bangkok, though, I found its shadows came into sharper focus. So much clearer than what is actually happening on a global scale. It's a spectacle of lights and shadows that I want to expose here on Bassifondi.

“Overshadow”. This is the oft-repeated mantra and the formula for understanding the Asia-Europe Meeting (ASEM). In a certain sense, it was like attending a production of what in Southeast Asia is known as the “theatre of shadows”, the Cambodian “Sbaek Thom”: every shadow can tell a story and the puppeteers themselves question the meaning of the shadows they create.

The tenth edition of ASEM, the two-yearly forum launched in 1996 to reinforce cooperation and dialogue between Europe and Asia, was held in Milan, Italy, in October. It was attended by Heads of State, ministers and civil servants from 53 countries: 29 from the European Union plus Norway and Switzerland, and 22 Asian countries. Together, ASEM members account for 62.5 percent of the world’s population, 57 percent of global GDP and 60 percent of global trade. “Responsible partnership for sustainable growth and security” was the theme of this “informal platform for dialogue”: such a vast topic can lend itself to all manner of discussions on economic, political, cultural, climate and energy issues.

There were so many people and so many discussions, of which only fleeting visions and vague information were glimpsed, created a shadowy effect. In Cambodia, at the 2012 ASEAN Summit, in Bangkok where I live, at other international meetings, I saw how hard it is to decode the webs of power. But in Milan, in my home country, it was even harder. Probably because here it was more complex to establish a boundary between East and West: “What is Asia? Where does Europe end? Where do they meet or collide?”, were not rhetorical questions: at ASEM Russia came under the Asian countries while the president of Mongolia called his remote country – which will host ASEM in 2016 - a “bridge between Europe and Asia”.

In a certain sense, Russian President Vladimir Putin's geopolitical strategy, Eurasia, seemed to hold sway. Located between Western and Eastern Europe (i.e. Central Asia) and bordered to the east by Mongolia, this is the theatre in which Russia can play a proactive role in the new round of “The Great Game” (as defined in 1898 by Lord Curzon, Viceroy of India, in reference to the murky conflict between Great Britain and Russia for control of Asia). China reacts to Russia's moves with plans for a “New Silk Road”, which connects the Middle Kingdom to Germany over land via Kazakhstan, Belarus, Poland and connects with the Maritime Silk Road via Italy or Spain.

As was revealed at ASEM, all this does not help bring Europe and Asia closer together. “We talk about global interdependence, and it is real. But while, whatever the economic dynamics, each region is intellectually aware of what is going on at the other end of Eurasia, each sees the other as distant and ultimately unconnected from its concerns,” wrote George Friedman, CEO of the private intelligence corporation Stratfor.

The contemporary Great Game, then, would be more appropriately named “Tournament of Shadows”. At ASEM, the biggest shadow was cast by the crisis in Ukraine, which overshadowed any other issues. Vladimir Putin and Ukraine President Petro Poroshenko met to discuss a possible solution. To no avail. To justify “Much Ado About Nothing”, José Manuel Barroso, current President of the European Commission (until November 2014), pointed out that "it was right to discuss Ukraine here", as though the discussion could raise the meeting's profile. The real justification is that the crisis in Ukraine may increase the risk of volatility of financial markets that could impact Asia and Europe. "Stability and peace are fundamental for the economy," declared Herman Van Rompuy, President of the European Council (until December 2014).

In the Theatre of Shadows the most brightly lit scene was the economy. Despite the followers of conspiracy theory, the hundreds of Asian and European entrepreneurs attending the Asia-Europe Business Forum (AEBF), which coincided with ASEM, all agreed on the liberalisation of economies. "Europe needs Asia. A strong Asian economy is a driver for global growth. At the same time, Asia needs Europe, its technologies and its markets," declared Van Rompuy. "From an economic point of view, Asia has become the largest trading partner of the European Union, which remains the world's largest single economy. Future growth in Asia, therefore, depends on access to European markets." For Asia's part, Benjamin Philip Romualdez, President of Chamber of Mines of the Philippines, pointed out "Our growth is your opportunity". Indeed, in this second phase of globalisation (in which consumption, more than output, is shifting Eastwards), managing to compete successfully will be decisive for Europe.

In fact, Europe must attract China’s Super-consumers more than Asia in general. Due to its enormous economic surplus, China's strategies are changing: it is giving up on short-term profit and investing huge amounts of capital. The activism of premier Li Keqiang at ASEM and on the other stops on his European tour demonstrated this. China is making the most of what Li calls a “global economic recession” to acquire business bases in the Old Continent, where the price of companies has dropped and more than one government has requested help from Beijing. The Chinese premier demonstrated yet more Soft Power in his meetings with Vietnamese premier Nguyen Tan Dung, shoring up bilateral relations and strengthening trade links. Thailand has also been offered collaboration: taking advantage of the European halt on commercial negotiations following last May's coup d'état, Li pledged to cooperate with Thailand in developing roads and basic infrastructure.

In short, bilateral agreements were one of the most evident features of ASEM. Which also represents its dark side. Not so much because of the secrecy involved, but mainly because they overshadow ASEAN. The Association cannot propose itself as a sole interlocutor. In 2009 the European Commission decided to redirect its goal, placing greater emphasis on bilateral agreements with individual members of the Association, and at ASEM the European Union remained sceptical. The 2015 ASEAN Business Outlook Survey highlighted the widespread concern that the much-anticipated ASEAN Economic Community (AEC) would not be launched by the end-2015 deadline. Too many of the specified deadlines of AEC implementation have been missed and some major initiatives have not taken off. According to some observers, this is partly down to ASEAN's inability to act as a supranational organisation. For others, especially the Germans (who perhaps fear an Asian repeat of European discord), one of the biggest obstacles to the ASEAN economic community is the presence of CLMV, i.e. Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar and Vietnam - countries that will need more time to adapt to this new economic space.

Offsetting this, the European Union has pressed the accelerator on the Free Trade Agreement (FTA) between ASEAN and EU - a move aimed at countering two other hyper-agreements: the American Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) and the Chinese Comprehensive Economic Cooperation in East Asia. In ASEAN the biggest supporter of the FTA with Europe is Malaysia, which will have the presidency of ASEAN in 2015. "Malaysia will take the lead to encourage the FTA process, which was discontinued a few years ago. We hope there will be an ASEAN-EU FTA that will complete the regional integration," declared Prime Minister Datuk Seri Najib Razak.

Ahead of these macro-agreements, ASEM has forged relations that may appear marginal in the global scenario, but are fundamental for regional integration. For example, between Cambodia and Thailand. The two premiers, Hun Sen and Prayut Chan-o-cha, held their first bilateral talks, demonstrating “the right chemistry” in pushing their cooperative friendship to a new level. According to well-informed sources, the two premiers discussed the development of special economic zones (SEZ), roads, customs facilities and crossings along the border. General Prayut proposed the setting up of an initial SEZ near Cambodia’s Poipet, while Cambodian authorities will consider setting up a similar estate in their territory to boost trade. And the shared desire to set up a joint development area (JDA) in the Gulf of Thailand was an open secret.

Shadows are often misleading. What might seem overshadowed may eclipse the global threat of “Super Chaos”.

The dark side of globalisation

10/12/14 17:38 Filed in: South-East Asia

The Golden Triangle: the territory formed by the great Mekong River on the borders of Laos, Burma and Thailand. The opium poppy grows well in the alkaline soil formed from the silt of this stretch of river and it is this fact that gives the region its name.

Today the Golden Triangle is a tourist destination attracting travellers in search of adventure. It's a reassuring image, almost a marketing strategy, especially where Thailand is concerned. In Laos and Burma, however, year-on-year opium cultivation is increasing. According to the Southeast Asia Opium Survey conducted by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) and released on 8th December, cultivation rose from 61,200 hectares in 2013 to 63,800 in 2014, the eighth consecutive year of growth and triple the amounted harvested in 2006.

The triangle has evolved into a graph - a set of interconnected points extending over the entire so-called “Greater Mekong Subregion”, which includes the Chinese province of Yunnan, Burma, Thailand, Laos, Cambodia and Vietnam and which, in turn, fits into the global market system.

The Golden Triangle imports the chemical products needed to transform opium into heroin, which is then exported to China, Southeast Asia and the rest of the world. The exchange is gradually facilitated by the developing infrastructure, and the reduced commercial barriers and frontier controls.

The Golden Triangle symbolises the dark side of globalisation, as defined by Giovanni Broussard, the Italian Programme Officer for UNODC's initiative on Border control and transnational organized crime, a 90 billion dollar business.

The enormity of that figure (which refers to all “Transnational Organized Crime”) confirms the last, macroscopic connection: that between the power of the traffickers and the impotence of the populations involved (especially in opium cultivation), who have no economic alternative and find themselves in the midst of ethnic or territorial disputes.

Southeast Asia Opium Survey 2014. Il Full Report

Border Control in the Greater Mekong Sub-region. Full Report

Today the Golden Triangle is a tourist destination attracting travellers in search of adventure. It's a reassuring image, almost a marketing strategy, especially where Thailand is concerned. In Laos and Burma, however, year-on-year opium cultivation is increasing. According to the Southeast Asia Opium Survey conducted by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) and released on 8th December, cultivation rose from 61,200 hectares in 2013 to 63,800 in 2014, the eighth consecutive year of growth and triple the amounted harvested in 2006.

The triangle has evolved into a graph - a set of interconnected points extending over the entire so-called “Greater Mekong Subregion”, which includes the Chinese province of Yunnan, Burma, Thailand, Laos, Cambodia and Vietnam and which, in turn, fits into the global market system.

The Golden Triangle imports the chemical products needed to transform opium into heroin, which is then exported to China, Southeast Asia and the rest of the world. The exchange is gradually facilitated by the developing infrastructure, and the reduced commercial barriers and frontier controls.

The Golden Triangle symbolises the dark side of globalisation, as defined by Giovanni Broussard, the Italian Programme Officer for UNODC's initiative on Border control and transnational organized crime, a 90 billion dollar business.

The enormity of that figure (which refers to all “Transnational Organized Crime”) confirms the last, macroscopic connection: that between the power of the traffickers and the impotence of the populations involved (especially in opium cultivation), who have no economic alternative and find themselves in the midst of ethnic or territorial disputes.

Southeast Asia Opium Survey 2014. Il Full Report

Border Control in the Greater Mekong Sub-region. Full Report

The arrogance of ignorance

25/11/14 15:33 Filed in: Logbook

Taiji Quan: meaning supreme ultimate (Taiji) boxing or fist (Quan). It is more widely known as Tai Chi and is practised as a gentle form of exercise and breathing technique. Many people know about it and have tried it. Very few know about Thai Chi. Just one person, in fact. The unknown author of a short article published on an online journal. The article seems to meld together two different concepts - Tai Chi and Muay Thai, i.e. Thai boxing (Muay). It's not a mistake. It is a demonstration of ignorance. Which paradoxically becomes cultural arrogance in its condemnation of a discipline practised even by children (for over a thousand years). Of course, the regime is harsh and often the children are being paid to fight. But they are not “instigated” by their parents, as the article claims. You only have to see the respect these children command in Thailand to know that. As well as the complex codes regulating family relationships. And the training the village children go through, which they see as play as well as an initiation rite. You would have to look outside the politically correct box. You would have to... But it's useless trying to explain in desperate cases such as this.

But this case is useful for one thing - as a paradigm for the new journalism: widespread, participatory, all-understanding and all-knowing, in which everyone knows everything and creates a world to resemble themselves…

…A world in which nothing is considered as something, emptiness as fullness. (Confucius).

But this case is useful for one thing - as a paradigm for the new journalism: widespread, participatory, all-understanding and all-knowing, in which everyone knows everything and creates a world to resemble themselves…

…A world in which nothing is considered as something, emptiness as fullness. (Confucius).

Archetypes

06/11/14 11:27 Filed in: Logbook

It took me a few days but in the end I understood: motorbikes are like warships.

I realised this at the Ducati 2015 World Première, at which new bikes from the global brand are presented for the very first time. The idea that warships and advanced naval weaponry systems reminded me of something came to me at Euronaval, the largest naval defence trade show. I kept wondering about it as I watched these presentations of weaponry systems or the maritime surveillance network, Marsur.

I watched the series of images, which looked like so many videogames or MTV videos, and tried to pin down the style of the show. I was immersed in an augmented reality in which my perceptions were amplified by the very fact that I was close to instruments designed to expand sensory capacities.

Sometime later I attended the Ducati première, quite by chance and out of personal curiosity. And in the promo films and technical specs of the motorbikes I recognised the same emotions – the same nervous system reactions – I had experienced at Euronaval.

The similarities could also extend to semantics (for example the use of the term “configuration”) and materials (carbon fibre first and foremost for its appearance).

But the closest and yet the most ambiguous comparison leads me to consider motorbikes and weapons as expressions of our species' primary drives, the materialisation of myths, cultural archetypes. James Hillman, the philosophical and psychological visionary who passed away a few years ago, would call them the “constants of the human dimension”. All too human.

About similarities: listen to the two soundtracks

I realised this at the Ducati 2015 World Première, at which new bikes from the global brand are presented for the very first time. The idea that warships and advanced naval weaponry systems reminded me of something came to me at Euronaval, the largest naval defence trade show. I kept wondering about it as I watched these presentations of weaponry systems or the maritime surveillance network, Marsur.

I watched the series of images, which looked like so many videogames or MTV videos, and tried to pin down the style of the show. I was immersed in an augmented reality in which my perceptions were amplified by the very fact that I was close to instruments designed to expand sensory capacities.

Sometime later I attended the Ducati première, quite by chance and out of personal curiosity. And in the promo films and technical specs of the motorbikes I recognised the same emotions – the same nervous system reactions – I had experienced at Euronaval.

The similarities could also extend to semantics (for example the use of the term “configuration”) and materials (carbon fibre first and foremost for its appearance).

But the closest and yet the most ambiguous comparison leads me to consider motorbikes and weapons as expressions of our species' primary drives, the materialisation of myths, cultural archetypes. James Hillman, the philosophical and psychological visionary who passed away a few years ago, would call them the “constants of the human dimension”. All too human.

About similarities: listen to the two soundtracks

The last frontier

07/10/14 15:57 Filed in: Logbook

Borneo has been called “the last frontier bordering on myth”. I have crossed the frontier of that myth many times. Each time it was harder to come out of it, with the body and the mind. Once I risked not coming out at all. Not in one piece, at least. It is chiefly the mind that gets lured into a web of sensations, visions and dreams; after two weeks there, you can't get out of it.

I am thinking about this again because an old friend has asked me to contribute towards a book on Italians in the Pacific. I chose to write a chapter on Odoardo Beccari, a naturalist from Florence who, between 1865 and 1878, explored the forests of far Southeast Asia. He was often isolated for months at a time. This is how he described the forest: “Infinite and varied are the aspects under which it presents itself, as are the treasures it conceals…Its mystery, sacred to science, rewards the believer equally as much as it does the investigative philosopher.” You understand why his writings inspired Salgari. But Beccari is not a character from a Salgari novel. He is more complex, as is revealed in his book, “In the forests of Borneo”, written with passionate, philosophical and even poetic words. He is more similar to certain Conrad characters, or Conrad himself.

As I do my research on Beccari, I discover new stories and come across others lost amongst my papers, bringing back memories of books read and journeys made. An intrigue of plots and characters forms, featuring seas, forests and rivers, sandbanks and deep oceans, pirates and pirate hunters, privileged gentlemen and unlucky adventurers, traders, explorers, old carts and Land Rovers.

Lost in this library of Babel, I think the only way to get out is to embark on a new path - any one will do. Perhaps beginning with these Bassifondi. Before my memory of them is also lost, the dreams merging with nightmare and the visions with ghosts.

Borneo - according to the introduction to Conrad's “Almayer's Folly” - is one of those scenarios that are a “metaphor for the actions happening there”.

I am thinking about this again because an old friend has asked me to contribute towards a book on Italians in the Pacific. I chose to write a chapter on Odoardo Beccari, a naturalist from Florence who, between 1865 and 1878, explored the forests of far Southeast Asia. He was often isolated for months at a time. This is how he described the forest: “Infinite and varied are the aspects under which it presents itself, as are the treasures it conceals…Its mystery, sacred to science, rewards the believer equally as much as it does the investigative philosopher.” You understand why his writings inspired Salgari. But Beccari is not a character from a Salgari novel. He is more complex, as is revealed in his book, “In the forests of Borneo”, written with passionate, philosophical and even poetic words. He is more similar to certain Conrad characters, or Conrad himself.

As I do my research on Beccari, I discover new stories and come across others lost amongst my papers, bringing back memories of books read and journeys made. An intrigue of plots and characters forms, featuring seas, forests and rivers, sandbanks and deep oceans, pirates and pirate hunters, privileged gentlemen and unlucky adventurers, traders, explorers, old carts and Land Rovers.

Lost in this library of Babel, I think the only way to get out is to embark on a new path - any one will do. Perhaps beginning with these Bassifondi. Before my memory of them is also lost, the dreams merging with nightmare and the visions with ghosts.

Borneo - according to the introduction to Conrad's “Almayer's Folly” - is one of those scenarios that are a “metaphor for the actions happening there”.

History and Fantasy

08/07/14 16:43 Filed in: South-East Asia

“Understanding is not the ability to answer any question, but the attempt to engage fully with the question… These questions are the presupposition for sapiential understanding”. This is one of any number of quotes to be taken from the monumental work by Elemire Zolla, “Il conoscitore dei segreti”, one of the greatest intellectuals of the 20th century.

"How are cities born? Why does a village grow into a city? This teaches us the mechanisms of history." These are the questions that inspired the research of Italian archaeologist Patrizia Zolese, “The Lady of Lost Cities”.

The two characters belong to distant philosophical and spiritual dimensions. But, as in parallel universes, they co-exist and are connected by gateways in the space-time continuum. In their case, that gateway is in the ancient East.

“The course of history depends less on what actually happens than on the falsehoods people believe,” wrote historian Felipe Fernandez-Armesto, thus offering another gateway. It's one way of explaining the previous connection. Zolese's research is perfect for constructing mental representations: temples, monuments or entire cities of long-gone civilisations are not only pieces of stone in the domain of history. They are a gateway to stories, even fantastical ones. And Zolla, that connoisseur of secrets, seemed to me to be a character that could introduce the meaning, or the sapiential perspective, of Zolese's research.

Other characters and other histories could come in at this point: the situation in the South China Sea on the routes of the ancient Cham merchants, the explorations into the deep jungle of the sacred mountain that dominates the Lao coast of Mekong, the things that inspired Kipling on his Road to Mandalay. These are all mental representations constructed on Patrizia's research. All of them are in places that, thanks in part (if not entirely) to her (as the Lerici Foundation's head of archaeology and culture for Asia), have become World Heritage sites: the Vat Phu site, in southern Laos, called the “cradle of the Khmer civilisation”; My Son, on the central coast of Vietnam, one of the most important centres of the ancient kingdom of Champa. Finally, the sites of the cities of the ancient kingdom of Pyu, in central Myanmar (better known as Burma).

Patrizia calls it "one of the greatest civilisations in Southeast Asia". "One of those populations that change things." Once again, history and its representations seem to meet: last June, the ancient cities of Pyu became Myanmar's first World Heritage Site.

As Patrizia says: "In the end my job can be summed up in two words: logos and archeo." Archeo in Greek means ancient. Logos means reason, but also story.

"How are cities born? Why does a village grow into a city? This teaches us the mechanisms of history." These are the questions that inspired the research of Italian archaeologist Patrizia Zolese, “The Lady of Lost Cities”.

The two characters belong to distant philosophical and spiritual dimensions. But, as in parallel universes, they co-exist and are connected by gateways in the space-time continuum. In their case, that gateway is in the ancient East.

“The course of history depends less on what actually happens than on the falsehoods people believe,” wrote historian Felipe Fernandez-Armesto, thus offering another gateway. It's one way of explaining the previous connection. Zolese's research is perfect for constructing mental representations: temples, monuments or entire cities of long-gone civilisations are not only pieces of stone in the domain of history. They are a gateway to stories, even fantastical ones. And Zolla, that connoisseur of secrets, seemed to me to be a character that could introduce the meaning, or the sapiential perspective, of Zolese's research.

Other characters and other histories could come in at this point: the situation in the South China Sea on the routes of the ancient Cham merchants, the explorations into the deep jungle of the sacred mountain that dominates the Lao coast of Mekong, the things that inspired Kipling on his Road to Mandalay. These are all mental representations constructed on Patrizia's research. All of them are in places that, thanks in part (if not entirely) to her (as the Lerici Foundation's head of archaeology and culture for Asia), have become World Heritage sites: the Vat Phu site, in southern Laos, called the “cradle of the Khmer civilisation”; My Son, on the central coast of Vietnam, one of the most important centres of the ancient kingdom of Champa. Finally, the sites of the cities of the ancient kingdom of Pyu, in central Myanmar (better known as Burma).

Patrizia calls it "one of the greatest civilisations in Southeast Asia". "One of those populations that change things." Once again, history and its representations seem to meet: last June, the ancient cities of Pyu became Myanmar's first World Heritage Site.

As Patrizia says: "In the end my job can be summed up in two words: logos and archeo." Archeo in Greek means ancient. Logos means reason, but also story.

A post-modern coup

10/06/14 17:01 Filed in: South-East Asia

“How do you interpret the Thai military strategy towards the media? Why is it so important for them to control the TV and journalists?”. I was asked this question a few days ago by a young journalist from one of the world's major television networks. A stupefying question, literally. The journalist's candid stupor astounds me: why is it important to control information following a coup d'état??!!

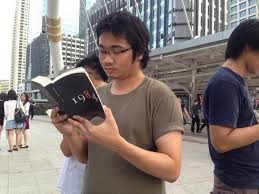

It has always been this way. Without studying the classics (whether it be Sun Tzu or Machiavelli), we need only browse through an interesting book by Edward N. Luttwak: Coup d'État: A Practical Handbook. Published in 1968, at a time when coups d'état were much more common and the concept of information more in-depth. Information in the age of social media seems confirmation of the uncertainty principle. Information cannot be fast and in-depth at the same time.

The Thailand of the coup d'état, and Bangkok in particular, is becoming a laboratory where this phenomenon of quantistical politics is occurring. Few protesters observed a great deal by a hail of photographers, reporters and operators. Communication via Twitter is more useful to the journalists for finding out where the protesters are than to the protesters themselves. A distortion of the observed object, and therefore of communication, is bound to follow. As demonstrated by the stupefying question: the effect (control) conceals the cause (the seizing of power). A lack of depth also justifies another distortion of the reality: the one in which photos from 2006 and 2010 are used simply because they are more dramatic or because they feature tanks in the street.

This is a post-modern coup in every sense. The few protesters on the streets of Bangkok, mainly at the weekend, use increasingly creative ways to show their dissent, inspired by messages and forms taken from global culture. Such as the “revolutionary” salute taken from the film The Hunger Games, reading George Orwell's 1984 in small groups (so as not to infringe the martial law), the “sandwiches for democracy” (“we're just eating a sandwich” said the university students held for infringing martial law). Not to mention that, immediately after the coup, one of the emblems of the opposition was Ronald McDonald, the fast-food chain's clown mascot, simply because the protesters used to hang out there.

As for the military, they have adopted an “overt and covert” strategy, which is a reworking of the hard-soft approach inherent in all Asian culture and martial arts.

Overtness, or softness, is expressed above all in the “return happiness to the people” operation, based on the idea of gross national happiness. The indicator of well-being was adopted several years ago in the Himalayan state of Bhutan and has become a model of Buddhism-inspired economic policy, as well as a happy example of marketing.

The Thai junta has an ambitious plan to return happiness to the people: economic measures (some already supported by the deposed government) in support of the poorer classes and farmers. Re-launching of great works (high speed, flood prevention). Campaign against corruption and for transparency in public officials' income. Improvement of public services. Promotion of domestic tourism (with low cost tour operators). The military has also launched a campaign of national pride, which pits Asian values (those supported by China) against those that the West slightly arrogantly insists on calling “universal”.

Considering the Thai vocation for “sanuk”, or fun, happiness is also pursued with concerts, shows, female dancers in mini-fatigues, free food stalls and even a barber service. Also in the name of fun and with a nod to the tourists, the curfew has been cancelled at holiday destinations and in places where “full moon parties” have been scheduled.

Wilawan Watcharasakwet/The Wall Street Journal

All this makes unhappiness look like a sin, like an antisocial, nihilistic protest by those who do not credit the military for bringing order back to the country. More than Orwell's 1984, it's more a case of Huxley's Brave New World.

A more hidden, harder aspect manifests itself in the repression of all dissent, even minimal, in the limitation of rights and civil liberties, in control of the media and even more of education. More worrying still is the ability to convince arrested protesters to sign a sort of abjuration. Which has happened despite detention periods being very short in many cases and, as the former detainees admitted, “a kind of holiday”. Perhaps the unspoken is the most powerful mechanism of psychological pressure, at least for the Asian mind. Teamed with an awareness that, if the confrontation degenerates, there is no more room for agreement.

As far as public opinion is concerned, the real flop was when Facebook was blocked for half an hour. It should have been a warning. But it backfired on the military: the reaction of millions of users was ferocious. Not because they felt their freedom of expression had been under threat, but because they were no longer able to message friends, post photos, arrange appointments, set up meetings and share them.

It has always been this way. Without studying the classics (whether it be Sun Tzu or Machiavelli), we need only browse through an interesting book by Edward N. Luttwak: Coup d'État: A Practical Handbook. Published in 1968, at a time when coups d'état were much more common and the concept of information more in-depth. Information in the age of social media seems confirmation of the uncertainty principle. Information cannot be fast and in-depth at the same time.

The Thailand of the coup d'état, and Bangkok in particular, is becoming a laboratory where this phenomenon of quantistical politics is occurring. Few protesters observed a great deal by a hail of photographers, reporters and operators. Communication via Twitter is more useful to the journalists for finding out where the protesters are than to the protesters themselves. A distortion of the observed object, and therefore of communication, is bound to follow. As demonstrated by the stupefying question: the effect (control) conceals the cause (the seizing of power). A lack of depth also justifies another distortion of the reality: the one in which photos from 2006 and 2010 are used simply because they are more dramatic or because they feature tanks in the street.

This is a post-modern coup in every sense. The few protesters on the streets of Bangkok, mainly at the weekend, use increasingly creative ways to show their dissent, inspired by messages and forms taken from global culture. Such as the “revolutionary” salute taken from the film The Hunger Games, reading George Orwell's 1984 in small groups (so as not to infringe the martial law), the “sandwiches for democracy” (“we're just eating a sandwich” said the university students held for infringing martial law). Not to mention that, immediately after the coup, one of the emblems of the opposition was Ronald McDonald, the fast-food chain's clown mascot, simply because the protesters used to hang out there.

As for the military, they have adopted an “overt and covert” strategy, which is a reworking of the hard-soft approach inherent in all Asian culture and martial arts.

Overtness, or softness, is expressed above all in the “return happiness to the people” operation, based on the idea of gross national happiness. The indicator of well-being was adopted several years ago in the Himalayan state of Bhutan and has become a model of Buddhism-inspired economic policy, as well as a happy example of marketing.

The Thai junta has an ambitious plan to return happiness to the people: economic measures (some already supported by the deposed government) in support of the poorer classes and farmers. Re-launching of great works (high speed, flood prevention). Campaign against corruption and for transparency in public officials' income. Improvement of public services. Promotion of domestic tourism (with low cost tour operators). The military has also launched a campaign of national pride, which pits Asian values (those supported by China) against those that the West slightly arrogantly insists on calling “universal”.

Considering the Thai vocation for “sanuk”, or fun, happiness is also pursued with concerts, shows, female dancers in mini-fatigues, free food stalls and even a barber service. Also in the name of fun and with a nod to the tourists, the curfew has been cancelled at holiday destinations and in places where “full moon parties” have been scheduled.

Wilawan Watcharasakwet/The Wall Street Journal

All this makes unhappiness look like a sin, like an antisocial, nihilistic protest by those who do not credit the military for bringing order back to the country. More than Orwell's 1984, it's more a case of Huxley's Brave New World.

A more hidden, harder aspect manifests itself in the repression of all dissent, even minimal, in the limitation of rights and civil liberties, in control of the media and even more of education. More worrying still is the ability to convince arrested protesters to sign a sort of abjuration. Which has happened despite detention periods being very short in many cases and, as the former detainees admitted, “a kind of holiday”. Perhaps the unspoken is the most powerful mechanism of psychological pressure, at least for the Asian mind. Teamed with an awareness that, if the confrontation degenerates, there is no more room for agreement.

As far as public opinion is concerned, the real flop was when Facebook was blocked for half an hour. It should have been a warning. But it backfired on the military: the reaction of millions of users was ferocious. Not because they felt their freedom of expression had been under threat, but because they were no longer able to message friends, post photos, arrange appointments, set up meetings and share them.